Weak enforcement of debt contracts can have undesirable consequences for financial development, as difficulty in recovering claims from distressed firms causes banks to reduce lending. Leveraging the staggered implementation of debt recovery tribunals across Indian states, this article shows that the legal reform had a positive impact on product growth in firms – as such innovation require considerable upfront investment and access to credit.

Developing countries are characterised by weak enforcement of debt contracts due to long delays in the liquidation proceedings and limited expertise in solving debt recovery cases by courts (Djankov et al. 2008). This can have undesirable consequences for financial development in the economy as banks reduce lending due to the difficulties in recovering claims from distressed firms. Recent research finds a positive link between debt contract enforcement and access to credit (Ponticelli and Alencar 2016). However, despite the importance of product innovation for economic growth, there is little evidence on the causal link between debt contract enforcement and product growth in the economy. In a recent study (Jain et al. 2021), we examine the effect of a legal reform targetting the efficiency of debt contract enforcement on product growth in the manufacturing sector in India.

Debt contract enforcement and product growth

Introducing new product lines entails considerable upfront investments, and financial constraints may force firms to operate in a sub-optimal number of product lines. Thus, the relationship between debt enforcement and firms' product growth depends on its effect on firm borrowing. On the one hand, efficient debt enforcement increases the liquidation value of the collateral that creditors can recover from defaulting firms and can also mitigate moral hazard problems in credit markets. Thus, efficient contract enforcement can increase access to credit for firms. On the other hand, an increase in the efficiency of debt enforcement can also discourage firms from investing in product innovation as it would increase the cost of failure due to the threat of premature and inefficient liquidation by creditors. Thus, whether efficient debt enforcement leads to increased borrowing, and in turn, product growth is an empirical question and depends on which channel dominates.

Why product growth?

We focus on product innovation as it is key to firm survival and growth, and firms must continually update their existing products and enter new product lines to preserve and expand their customer base. Further, other measures of innovation such as patents, fail to fully capture innovation activity in the product market. Even for developed economies like the US, only a small fraction of manufacturing firms (6.3%) use the patent system (Graham et al. 2018), and this share is likely to be even lower in developing countries that have weak protection of intellectual property rights. Finally, introducing new products is a complex process, and the knowledge generated through research needs to be supplemented with substantial upfront investments in product development, plant and machinery, advertisement, and distribution activities. Thus, firms' product scope may be more responsive to the relaxation of financial constraints as compared to investment in research activities. The introduction of new products by firms directly measures the outcome of innovation activity for all firms and helps us better capture the aggregate impact of debt enforcement on innovation through product creation in the economy.

Detailed data on product lines manufactured by firms is rarely available. However, in India, under the Companies Act, 1956, companies are required to report information on sales revenue and quantity for all product lines. For our study, we use CMIE (Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy) Prowess data from the period 1990-2004, which reports product-level information for all product lines manufactured by each firm over time. We compile data on product lines with other firm-level indicators to examine the effect of debt enforcement on product growth.

Debt recovery tribunals in India

The RDDBFI (Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions) Act, 1993 was enacted to improve the debt recovery for banks by introducing specialised courts for debt recovery. Debt recovery tribunals (DRTs) were supposed to be established across the country in 1993, however, only five tribunals were introduced in 1993 as the law was challenged in court, which halted the process for two years. The process of DRT establishment restarted after the interim ruling of the Supreme Court of India in favour of DRTs. The staggered implementation of DRTs across the states provides us the ideal setting to study the effect of debt enforcement on product growth.

Before introducing the RDDBFI Act, all loan recovery cases were processed in civil courts in India. Civil courts in India are prone to procedural delays – according to a 1998 Government of India report, more than 40% of the liquidation cases were pending for more than eight years in Indian civil courts. Consequently, a large proportion of bank funds was blocked in non-performing assets. To remove these legal bottlenecks in the recovery of bank dues, the Government of India passed the RDDBFI Act, 1993 to establish new specialised debt recovery courts across the country. These DRTs have significantly improved the efficiency of the debt recovery process (Visaria 2009).

DRTs and product growth

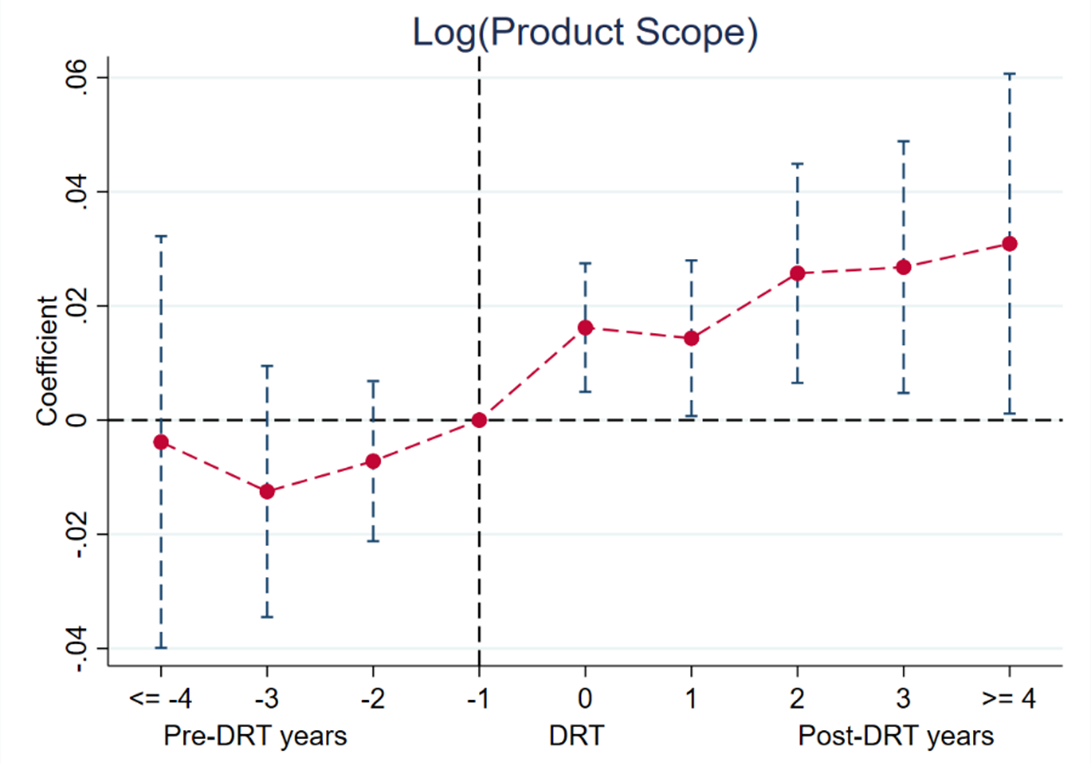

Our empirical strategy relies on comparing changes in firms' product scope before and after DRT implementation in DRT states to firms in non-DRT states. Our primary finding is that the establishment of DRTs led to an increase in the introduction of new product lines by firms. Figure 1 shows the yearly differential effect on firms’ product scope in DRT versus non-DRT states. We find that following the implementation of DRTs, firms increase their product scope by 2.4%, on average, accounting for 15% of the observed change in product scope during our study period.

Further, due to inelastic credit supply in the short run, only the firms with high tangible assets experience an increase in the credit, and consequently an increase in their product scope. We find that DRTs account for a 51% increase in the product scope of high tangible-asset firms during our study period. We also find that firms introduced new product lines in industries outside of their current scope of operation suggesting bolder innovation moves in response to DRTs. Introducing a product in a new industry requires large upfront investments in research and development (R&D), plant and machinery, and advertising and marketing. However, at the same time, it ensures firm growth, as new products are less likely to cannibalise the existing product lines of the firms.

Figure 1. Yearly differential product growth in DRT versus non-DRT states

DRTs and firm performance

We find that DRTs led to a significant increase in the sales of high tangible-asset firms. Further, we find that high tangible-asset firms experienced an increase in profitability, as measured by return on assets and operating margins, after the establishment of DRTs. Finally, we estimate the effect of DRTs on total factor productivity (TFP) of firms and the allocation of physical capital and labour across firms with differing TFP levels. We find evidence for an increase in firm-level TFP after the implementation of DRTs. We also find that DRTs led to the reallocation of capital and labour towards high TFP firms. Taken together, these results imply that DRTs have a positive impact on both product growth and productivity of firms.

Mechanism: Financial constraints

We find that the underlying mechanism that drives the effect of DRTs on product innovation is access to credit. Our findings suggest that high tangible-asset firms experienced an increase in leverage and total borrowings. Further, we find that the increase in the product scope is predominantly driven by firms in industries with higher external financial dependence, and younger firms that are likely to be more financially constrained. Our results also suggest that firms increased spending on the expenditures they need to undertake to introduce new products in the markets. Particularly, we find an increase in R&D expenditure, physical investment in plant, property, and equipment, and advertising and marketing expenditures.

Conclusion

Legal institutions, by protecting property rights and enforcing contracts, play an important role in the financial development and growth of an economy. However, the mechanisms underlying this relationship is not clear. Do firms grow by accumulating physical capital with the same technological know-how? Or do they grow by undertaking innovation activities that enable them to introduce new product lines and improve efficiency? Our study takes a step in addressing this gap and, to the best of our knowledge, provides the first causal evidence that an increase in the efficiency of debt contract enforcement leads to a significant increase in product scope and productivity of manufacturing firms in India. Thus, at least in India, legal institutions play an important role in funding firms’ innovation activities.

Further Reading

- Djankov, Simeon, Oliver Hart, Caralee McLiesh and Andrei Shleifer (2008), “Debt enforcement around the world”, Journal of Political Economy, 116(6): 1105-1149.

- Graham, Stuart J, Cheryl Grim, Tariqul Islam, Alan C Marco and Javier Miranda (2018), “Business dynamics of innovating firms: Linking US patents with administrative data on workers and firms”, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 27(3): 372-402.

- Jain, T, R Singh and C Subramanian (2021), ‘Debt Contract Enforcement and Product Innovation: Evidence from a Legal Reform in India’, IIM Bangalore Research Paper No. 649.

- Ponticelli, Jacopo and Leonardo S Alencar (2016), “Court enforcement, bank loans, and firm investment: evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(3): 1365-1413.

- Visaria, Sujata (2009), “Legal reform and loan repayment: The microeconomic impact of debt recovery tribunals in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3): 59-81.

Social media is bold.

Social media is young.

Social media raises questions.

Social media is not satisfied with an answer.

Social media looks at the big picture.

Social media is interested in every detail.

social media is curious.

Social media is free.

Social media is irreplaceable.

But never irrelevant.

Social media is you.

(With input from news agency language)

If you like this story, share it with a friend!

We are a non-profit organization. Help us financially to keep our journalism free from government and corporate pressure

0 Comments