The Netflix action flick has glaring factual inconsistencies despite its claim of being based on real life incidents. Here's what transpired between the two archrivals in the decades of the ‘70s and ‘80s.

In January 1987, India amassed nearly half a million troops in the Rajasthan province bordering Pakistan — ostensibly for a military exercise codenamed Brasstacks.

It was the largest armed mobilisation in South Asia and involved hundreds of tanks and armoured vehicles backed by air support. The drills were conducted a few kilometres from Sindh, the Pakistani province that borders Rajasthan.

Behind that military posture was the Indian army chief Lieutenant General Krishnaswami Sundarji, a known Pakistani hawk, who had for years raised concerns about Islamabad’s clandestine nuclear weapons programme.That’s the closest New Delhi ever got to undermining Pakistan’s nuclear ambition.

Exercise Brasstacks brought the armies of two countries close to a war. (AP Archive)

The military build up happened around the time when India was reeling from a violent insurgency in its province of Punjab, which was up in arms after security forces carried out an operation at the Golden Temple, a holy site of the Sikh minority, to drive out militants.

India accused Islamabad of supporting Sikh separatists who were demanding a territory of their own that they called Khalistan.

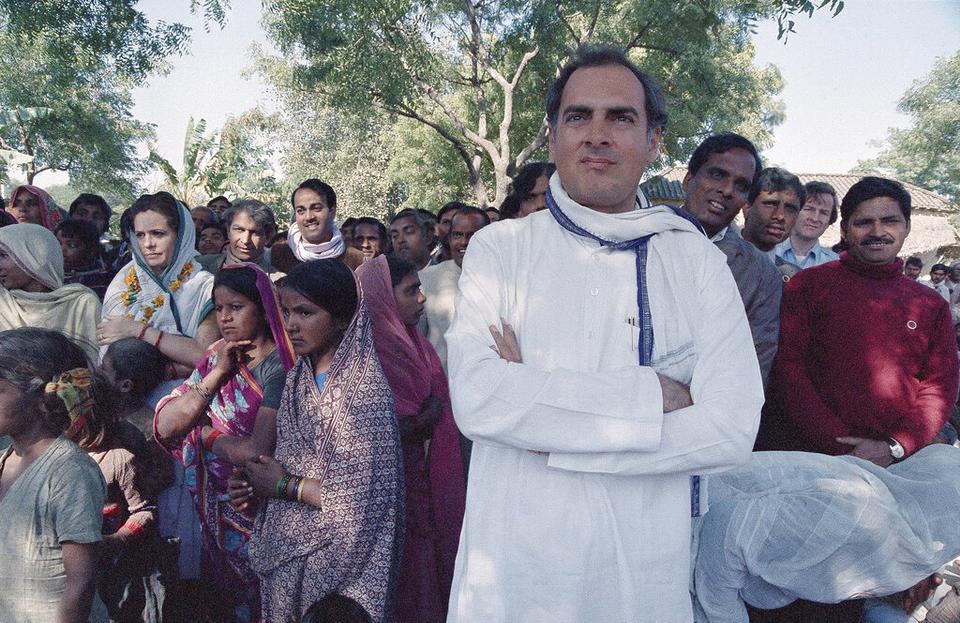

“Sundarji wanted to trigger a war and in garb of that, he was planning to strike Kahuta, the nuclear facility where weapons-grade uranium was being enriched,” says Feroz Khan, a professor of nuclear proliferation at the Naval Postgraduate School and author of ‘Eating Grass: the Making of the Pakistani Bomb.’“But a counter mobilisation by Pakistan worried then-Indian prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, who wasn’t properly briefed by Sundarji. The two sides eventually deescalated the situation.”

For decades, researchers have studied if New Delhi made any serious attempts to take out Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programme while it was in its infancy in the mid-1970s and mid-1980s.

The debate was given a fresh impetus in January with the release of an Indian movie on Netflix, ‘Mission Majnu.’

The action-packed Bollywood flick is about an Indian spy who infiltrates Pakistan, where he masquerades as a tailor, marries a blind Muslim woman and eventually comes close to his target, Kahuta. After gathering evidence about the secret nuclear facility, he single handedly fights off dozens of Pakistani soldiers. In the end, the protagonist, who is a Sikh, redeems his rebel father’s treachery, dying in a shootout after shouting “Hail Mother India.”

Many in Pakistan called it a ‘propaganda’ film, arguing that its plot was more comical than factual. The makers of the film insist it is inspired by ‘true events.’

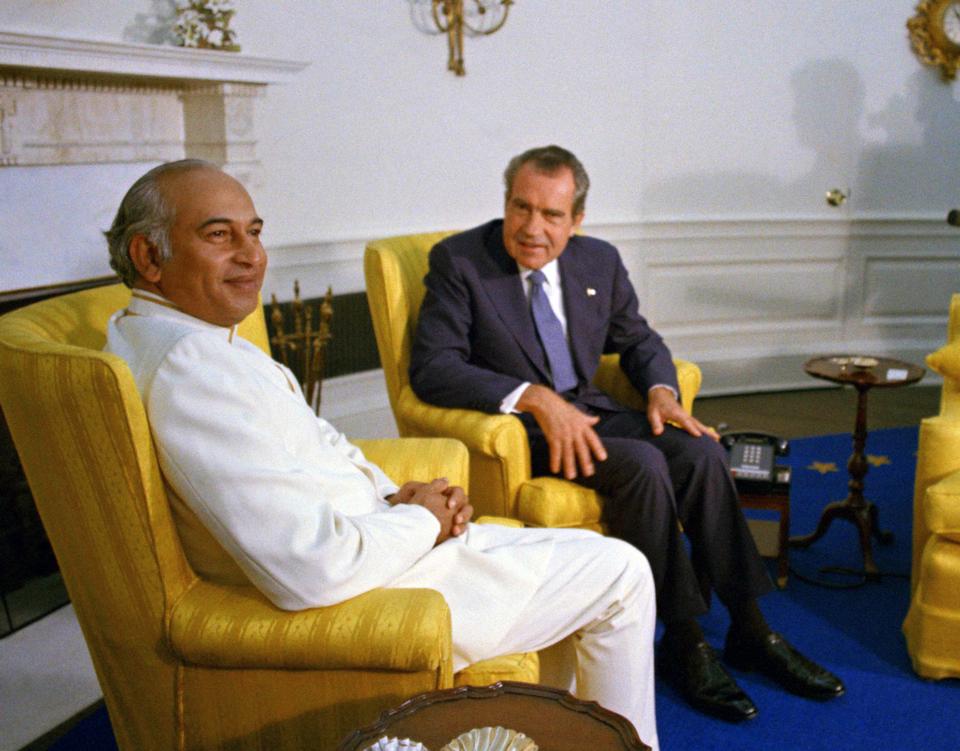

Behind the cinematic theatrics, there’s a real story about how India responded to Pakistan’s nuclear project. It’s serious and complicated. It’s a story of arrogance, disbelief, threats and diplomacy. And it all started with former Pakistani prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

‘We’ll feed on grass, even if we had to’

Bhutto was the foreign minister in 1965 when a journalist from the Manchester Guardian asked how Pakistan would react if India decided to build a nuke.

“If India makes an atom bomb, then even if we have to feed on grass and leaves — or even if we have to starve — we shall also produce an atom bomb as we would be left with no other alternative,” Bhutto said.

India had stepped up efforts to acquire technology to make a plutonium bomb after China conducted its first nuclear explosion in 1964.

It was a pivotal period for India and Pakistan as the two neighbours fought a bloody war in 1965 and both sides wanted to beef up their defences.

India became a nuclear power when it successfully tested its first nuclear bomb in 1974.

Bhutto, however, had to wait years before Pakistan came close to producing a bomb, according to Khan, who served as a brigadier in Pakistan’s army and for a time worked at the Strategic Plans Division, which is responsible for guarding the nuclear arsenal.

“Those initial efforts didn’t go anywhere until 1974, when Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan entered the picture,” says the professor.

Dr A Q Khan, known as the father of Pakistan’s nuclear programme, was a metallurgist who copied designs of German centrifuges while working in Europe and brought them back to Pakistan.

With a doctorate in copper metallurgy from the Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium, his expertise brought him in close contact with those developing centrifuges in a plant in Almelo, the Netherlands. That facility was run by URENCO Group, a nuclear fuel supplier.

Fluent in English, French and German, his managers would often ask him to translate German reports on centrifuge technologies. The importance of the sketches and details he saw didn’t escape his attention.

The blueprints weren’t enough to build a functional nuclear programme capable of producing weapons-grade uranium.

Only a handful of European companies that made critical parts and components such as vacuum pumps, valves and aluminium casing were willing to trade with Islamabad.

Spearheaded by A Q Khan, Pakistani diplomats, intelligence operatives and even A Q Khan’s friends set up shell companies around the world to buy those components. Whatever wasn’t available was produced locally.

Centrifuges rotate at twice the speed of sound to separate the U-235 isotope from U-238. Thousands of centrifuges operate in a cascade formation at the same time. Malfunction and failures were common in the initial years and Pakistani scientists learned how to master enrichment through trial and error.

A factual distortion in the Netflix film ‘Mission Majnu’ was centred around how Pakistan imported uranium. A key input for uranium enrichment — the process whereby weapons-grade uranium is produced — is the uranium hexafluoride (UF6) gas. Pakistan didn’t import uranium because of international scrutiny. It mined the key ingredient in the Baghal Chur area of the Dera Ghazi Khan district in 1975 and 1976 and produced its own UF6 gas.

In June 1978, Pakistani scientists were able to figure out how to successfully run the gas centrifuges. From here on, it was a matter of enriching the uranium so it could be used as fuel in a weapon.

But the cover of Pakistan’s nuclear programme and A Q Khan’s network of suppliers was blown in March 1979, when German broadcaster ZDF ran a documentary exposing how A Q Khan had stolen centrifuge designs while working in the Netherlands.

ZDF's documentary lumped Islam, the Middle East, A Q Khan and Israel’s national security together, weaving all four elements into an enticing conspiracy plot.

That’s when the catchphrase ‘Islamic Bomb’ became a media trope, writes Dr Malcolm Craig in his book ‘America, Britain and Pakistan’s Nuclear Programme 1974-1980.’

Yet most governments — including India’s — didn’t feel the urgency in the late 1970s to act because they deemed that a low-income country which had just lost its eastern wing (today's Bangladesh) lacked the capacity and skill to handle such sophisticated technology.

There was perhaps one exception: Israel.

Any real attempts to harm Pakistan’s nuclear programme were revealed when executives at European companies doing business with A Q Khan began receiving threats. Some even faced assassination attempts.

A letter bomb exploded at the home of Heinz Mebus in Erlangen, West Germany. Mebus, who had helped Pakistan build fluoride and uranium conversion plants, escaped unharmed, but his dog died in the explosion. A similar bombing targeted a senior executive of a Swiss company, CORA Engineering, which had also worked on Pakistan’s nuclear programme, codenamed 706.

Threatening letters were sent and phone calls made to European officials who were known to be working with A Q Khan. Little-known organisations such as the Group for Non Proliferation in South Asia propped up, claiming responsibility.

While Tel Aviv never acknowledged its role in the bombings, historians and researchers such as Adrian Levy and Catherine Scott-Clark, authors of a book on Pakistan’s nuclear programme, have blamed Israel’s foreign intelligence outfit Mossad.

“They didn’t want a Muslim country to have the bomb,” says Feroz Khan.

Saudi Arabia and Libya had, under Muammar Gaddafi, financially helped Pakistan’s nuclear programme, he adds.

Like Pakistan, Israel had also pilfered technology and know-how to make nuclear weapons. But while Pakistani nuclear scientist A Q Khan was later arrested and humiliated on national television for allegedly running an illegal proliferation network, the Israeli agent Arnon Mlichan was celebrated for his scientific feats without any state scrutiny or scorn.

Milchan, who stole European designs for centrifuges that were built at the Dimona nuclear facility in Israel, went on to become a famous Hollywood producer behind hit films such as ‘Pretty Woman’ and ‘Fight Club.’

Yet curiously enough, the Indian state didn’t take the neighbouring country’s enrichment attempt seriously until it was too late. At the heart of that underestimation was a superiority complex stemming from the Hindu caste system wherein Brahmins are considered better than all others.

“The Brahminical contempt for the abilities of Pakistan’s scientists and engineers also was intensified by the difficulties India’s well-educated had in trying to master large-scale uranium enrichment,” writes George Perkovish in his seminal book ‘India’s Nuclear Bomb.’

There are two ways to make a nuclear weapon — either through highly enriched uranium or plutonium. India took the plutonium route to make its first bomb. New Delhi announced archiving capability to enrich weapons-grade uranium in 1986.

The ‘myth’ of the Osirak contingency

“It was probably in 1981 that Indian intelligence started to pick up evidence that Pakistan was making the bomb,” says Sumit Ganguly, a political professor at the Indiana University Bloomington, who has written extensively on nuclear issues in South Asia.

In the years after they gained independence from British colonial rule in 1947, India and Pakistan struggled to boost their economies and take millions of people out of poverty.

New Delhi still boasted a much larger industrial base with the capability to indigenously produce cars and key metals.

“I have heard this independently from Indian analysts that the Indian scientific establishment believed that Pakistanis may have theoretical knowledge, but they don’t have the industrial capacity. That was arrogance on their part,” says Ganguly.

When it finally dawned on New Delhi that Pakistan was close to making a bomb, some military leaders, including Sundarji, pushed the government to take action.

One popular narrative that has made its way into history books centres around a secret Indian plan to use jets to blow up Kahuta, located some 40 kilometres from Islamabad.

As the story goes, at some point in 1981, India’s military prepared a squadron of its Jaguar jets to fly close to the terrain, infiltrate Pakistani territory and blow up the centrifuges.

Experts’ opinions differ as to whether such a plan was ever conceived.

That same year, an Israeli air raid destroyed a nuclear reactor at Osirak in Iraq. Some Indian military officials considered carrying out a similar strike against Kahuta as part of what they called the ‘Osirak contingency’.

“We never got clear-cut confirmation about such an operation. My view is that, yes, military officers felt it was their duty to offer certain military options to the political leadership and ultimately Indira Gandhi, then-Indian prime minister, said no to the plan,” says Ganguly.

Reports that the Indian air force was preparing to strike the Kahuta nuclear site matched a leaked US cable showing satellite images of a group of Indian Jaguar aircrafts that were missing from their designated air base.

But Pakistanis took the information seriously and sent their own jets on regular flights over Kahuta — just in case. But years later, an Indian Air Force officer laughed at the whole missing-Jaguar incident.

The planes were hidden in nearby woods as part of a passive air defence drill, writes Perkovich in ‘India’s Nuclear Bomb.’

About Pakistan’s air patrol over Kahuta, “We said fine, burn up your engines,” the Indian officer told Perkovish.

Militaries around the world draw up plans, prepare contingencies and run simulated war games, but that doesn’t constitute a precursor for an attack against an enemy, notes Ganguly.

“An Indian attack would have disastrous consequences with the OIC (the Organization of Islamic Countries). The OIC would have been absolutely furious,” he says.

Besides the funds that were flowing into Pakistan’s nuclear project from Saudi Arabia and other OIC members, it was the notion of Islamic solidarity that deterred New Delhi, he adds.

A perpetual threat

The fear of either side trying to hit each other’s nuclear facilities was real enough for both countries to take necessary precautions. India also beefed up air defences around its Trombay nuclear facility near Mumbai.

It was not only India and Israel that were interested in trying to find out how far Pakistan had progressed in making a bomb, however.

After the ZDF documentary disclosed A Q Khan’s activities, Robert Galluci, a senior US State Department official, tried to visit the Kahuta research facility to see what was happening there.

Situated close to the Pakistani capital, Kahuta is a small, scenic town where families often go to wind down. When Pakistani intelligence officials stopped Galluci, he said he was going to Kahuta for a picnic. He was nevertheless turned back.

But the then-French ambassador to Pakistan, Pol le Gourrierec, and his first secretary weren’t so lucky. They were beaten up by security officials when they attempted to get too close to Kahuta. The incident strained diplomatic ties between Paris and Islamabad.

Another incident related to foreign surveillance was rather bizarre. Workers near the centrifuge plant accidentally came across a rock that broke open and revealed wires and circuits protruding from inside.

“It was obvious it was planted by US intelligence. No one else could have done that,” says Feroz Khan.

The Brasstack tension of the mid-1980s deescalated after diplomatic negotiations.

In the mid 1990s, Pakistan and India signed an agreement promising not to attack each other’s nuclear facilities. Then, in 1998, both sides conducted nuclear tests, making a nuclear strike against each other a foregone conclusion.

In the ensuing years, the two archrivals, who were involved in border and air skirmishes as recently as 2019, built up an arsenal of hundreds of nukes and delivery systems, including long-range missiles.

But they have also taken steps to avoid any mishap, says Dr Mario Carranza, a political science professor at the Texas A&M University Kingsville.

“They have a commitment to notify each other before they test ballistic missiles. There’s also a de facto moratorium on nuclear testing because they haven’t tested nuclear weapons in years.”

New Delhi and Islamabad exchange locations of civilian nuclear facilities every year as a confidence-building measure.

A sign of how they can avoid any serious escalation came last year when an Indian cruise missile that had been accidentally launched landed deep inside Pakistan. The missile was not armed and no one was injured. Pakistani officials didn’t raise the issue in any international forum.

“But they have completely ignored nuclear arms control or even the possibility of seriously engaging in nuclear arms control. They are even modernising their nuclear arsenal,” says Carranza.

“So the Damocles sword continues to hang on millions of people in South Asia."

Saad Hasan

Social media is young.

Social media raises questions.

Social media is not satisfied with an answer.

Social media looks at the big picture.

Social media is interested in every detail.

social media is curious.

Social media is free.

Social media is irreplaceable.

But never irrelevant.

Social media is you.

(With input from news agency language)

If you like this story, share it with a friend!

0 Comments