In recent years, political parties in India have increasingly leveraged Whatsapp as a tool to reach voters, raising concerns about the influence of social media on the democratic process. This article looks at the interpersonal nature of social media and its ability to reach voters in the context of the 2021 elections in Tamil Nadu, and finds that political groups improve voter knowledge, without increasing negative feelings, and only sway the party preferences of moderates.

The political effects of social media have been hotly contested in democracies around the world. In the world’s largest democracy – India – the most popular social media platform is WhatsApp, a chat-based application with more than 500 million Indian users. As a result of its popularity, political parties and politicians have leveraged WhatsApp as a tool to reach voters. Yet little is known about the influences, positive or negative, that this platform has on the democratic process.

At its inception, social media was presented as an exciting new tool for people to connect with each other and learn about the world around them. Research in development economics showed that voter information interventions had the potential to improve policy outcomes (Pande 2011). Yet with time, we have seen that social media is often ideologically segregated, leading to concerns about the political effects of misinformation and polarisation on social media (Guriev et al. 2021).

What makes social media unique?

In a recent study (Carney 2022), I investigate how political groups on WhatsApp influence voters in a large election in Tamil Nadu, India. To understand how social media may affect voters, it is first important to outline how it differs from traditional media. The defining feature of social media is that users engage in what the literature refers to as ‘horizontal communication’ or two-way information sharing between users (Zhuravskaya et al. 2020). While traditional media involves primarily ‘vertical communication’– where information is shared from a common source with limited interaction, social media combines elements of vertical and horizontal communication.

Political actors use social media platforms – including WhatsApp – as a tool of mass media to broadcast their messages at a low cost. But unlike traditional campaigning, individual users can also reply and post themselves. My research aimed to understand the effect of social media groups on voters, but also to disentangle the effects of this vertical and horizontal communication. Put differently, I wanted to understand: does social media function in politics primarily as a tool for campaigns to reach more voters, or is the interpersonal nature of social media key to how it affects voters?

Testing the effects of political WhatsApp groups

To answer these questions, I conducted an experiment on WhatsApp in the context of Tamil Nadu’s 2021 Legislative Assembly Election. Across India, political parties campaign on WhatsApp by creating thousands of localised groups of up to 256 members1. This is a common campaign strategy in many of the world’s largest democracies2 where WhatsApp is popular (Garimella and Eckles 2020). In the most recent general election, one in six Indian voters reported being a member of such a group (Kumar and Kumar 2018).

Both leading parties in Tamil Nadu, the incumbent All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) and the challenger Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) adopted this strategy in the 2021 election, creating WhatsApp groups organised at the constituency level. I identified 25 constituencies around Chennai where both parties posted public invitation links for interested people to join their WhatsApp groups. Before my experiment began, these groups contained 94 members on average. Importantly, these groups featured vertical communication, with a small group of administrators posting official party campaign content, as well as horizontal communication, with individual group members permitted to post at will.

To measure the impact of group membership on voters, I recruited over 3,000 study participants on Facebook and randomly offered some participants links to join one of these WhatsApp groups. To isolate the effect of horizontal communication between users, I designed a second intervention. For each party-organised WhatsApp group I identified, I created a new, corresponding WhatsApp group. These new groups looked identical to the real groups, but the settings prevented individual members from posting. Instead, I created a web automation program that read messages sent to the real groups, identified the posts from party administrators, and then forwarded only these messages (and not the posts of individual group members) to the corresponding new groups. In this way, the new groups exposed participants to the exact party messaging they would have seen in the original groups, but not the posts and replies of other members.

After participants completed a brief baseline survey, they were randomly assigned to either the full WhatsApp groups, party-content-only groups, or a control condition where they did not join any group3. This randomisation allows for estimation of the impact of group membership. Comparing the real groups to the new groups gives the impact of horizontal peer messaging, above and beyond the impact of the vertical party messaging. The groups people were invited to corresponded to their reported voting constituency, and the party was determined randomly.

Roughly four weeks after the baseline survey, and immediately after the election, participants received an invitation to complete an endline survey, which measured the main experimental outcomes.

Findings

The first outcome examined is political knowledge, measured using a quiz where participants were asked about their belief in a series of true and false headlines. The experimental estimates show that the political WhatsApp groups in the study improved voter knowledge, making treated participants better able to distinguish true from false news. This result is notable considering concerns about political misinformation on social media, particularly on WhatsApp in India.

Each endline participant saw three kinds of new headlines: true headlines, taken from the news; rumors that circulated online and were debunked by prominent factcheckers; and false headlines that had not circulated online (written by research assistants). Regressions estimating the effects of the WhatsApp groups on voter knowledge found that scores on the quiz increased by 0.17 standard deviations4 in the full groups relative to the control. This increase came mainly from treated participants’ confidence in true headlines, which increased by 0.48 standard deviations relative to the control. Belief in rumors and false headlines also decreased, but point estimates are small and not significantly different from zero.

The second outcome is political preferences, to evaluate concerns about social media increasing polarisation. Endline participants completed a series of agree/disagree questions, which were then aggregated into a series of indices about political preferences. The results showed that treated participants’ relative rating of the assigned party increased by 0.072 standard deviations. This effect is driven by moderates, whose preferences moved toward the randomly assigned party as a result of WhatsApp group membership.

Treatment effects on policy preferences are similar, but smaller, and not statistically significant. Notably, there is no evidence of an effect on affective polarisation, that is, negative feelings toward members or supporters of the opposition party, which has increased due to social media in other contexts, such as the United States. (Iyengar and Krupenkin 2018, Levy 2021).

The effect of peer-to-peer messaging

These results suggest that the party-organised WhatsApp groups increased political knowledge, with small but significant impacts on the political preferences of moderates. But what about the participants in the second treatment group who received only direct party messaging?

Across all main outcomes, the effects of vertical party messaging by itself are consistently smaller in magnitude and less significant than the effects of the full groups with vertical party messaging and horizontal peer messaging. In aggregate, the difference between the effects of the full groups and party messaging alone is statistically significant. This suggests that the defining feature of social media – horizontal communication between peers – is precisely what makes these WhatsApp groups influential.

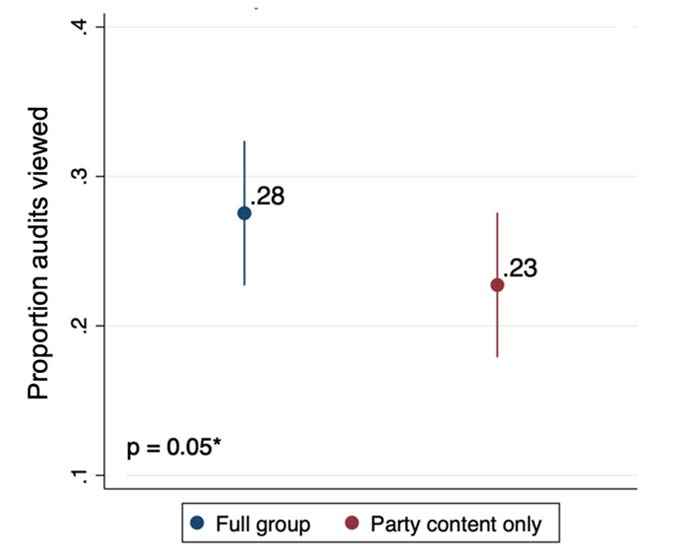

Administrative data from WhatsApp show that peer messaging serves to increase participants’ attention to the groups. These data include all posts that participants were exposed to and how quickly posts were viewed (using WhatsApp’s ‘seen by’ feature). Figure 1 shows that participants in the full groups with peer-to-peer messaging were significantly more likely to visit the groups and view a given message than people in groups with only party messaging. Consistent with this, participants in the full groups reported spending 16 minutes more on WhatsApp each day than participants in the party-content-only condition or the control. These results demonstrate that the horizontal communication in WhatsApp groups increases user engagement.

Figure 1. Participants’ attention by group

Note: Attention is measured using a series of audit messages, posted on the groups three times during the study, and WhatsApp’s ‘seen by’ feature. The outcome is the fraction of audit messages viewed within 48 hours.

Policy implications

On aggregate, the results of this research provide encouraging evidence on the influence of social media on voters. The political groups on WhatsApp studied in this paper improved voter knowledge, making group members better at distinguishing true from false news. Although the groups moved their members’ preferences towards the affiliated party, heterogeneity analysis suggests that the groups’ content was more tailored, or at least more convincing, to moderates than extremists. And there is no evidence of an increase in affective polarisation.

Considering widely held concerns about the influence of social media on the democratic process, this research provides a more optimistic result. However, important caveats apply. The leading parties in Tamil Nadu grew out of a common political movement, and as a result the political discourse in this context may be less inflammatory or divisive than in other settings. Additionally, WhatsApp’s architecture is distinct from other platforms such as Facebook or Twitter. For example, WhatsApp is not governed by an algorithm, and posts appear in users’ feeds chronologically. As a result, posts that are more engaged with – possibly due to their provocative nature – are more likely to go viral on a platform governed by an algorithm. The results of this research are likely sensitive to these contextual details. Further research on other kinds of social media groups in other settings will help assess the generalisability of the findings discussed here.

Notes:

- WhatsApp’s maximum group size

- Research has documented a large volume of political WhatsApp groups in Brazil (Bursztyn and Birnbaum 2019, Newman et al. 2019), and similar groups are common in Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines, for example.

- Of participants who were sent the WhatsApp group invitation link, 49% clicked to join the group offered. These 49% were then redirected either to the full group or party-content-only group in their WhatsApp application, or the last page of the survey (the control condition).

- Standard deviation is a measure that is used to quantify the amount of variation or dispersion of a set of values from the mean value (average) of that set.

Further Reading

- Burszytn, Victor S and Larry Birnbaum (2019), “Thousands of small, constant rallies: a large-scale analysis of partisan WhatsApp groups”, ASONAM '19: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining: 484-488.

- Carney, K (2022), ‘The Effect of Social Media on Voters: Experimental Evidence from an Indian Election’, Job Market Paper.

- Garimella, Kiran and Dean Eckles (2020), “Images and misinformation in political groups: Evidence from WhatsApp in India”, arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.09784.

- Guriev, Sergei, Nikita Melnikov and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya (2021), “3G Internet and Confidence in Government”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(4): 2533–2613.

- Iyengar, Shanto and Masha Krupenkin (2018), “The strengthening of partisan affect”, Political Psychology, 39: 201–218.

- Kumar, S and P Kumar (2018), ‘How widespread is WhatsApp’s usage in India?’, LiveMint, 18 July.

- Levy, Ro’ee (2021), “Social media, news consumption, and polarization: Evidence from a field experiment”, American Economic Review, 111(3): 831–70.

- Newman, N, L David and KN Rasmus (2019), ‘Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2019’, Technical Report.

- Pande, Rohini (2011), “Can informed voters enforce better governance? Experiments in low-income democracies”, Annual Review of Economics, 3(1): 215–237. Available here.

- Zhuravskaya, Ekaterina, Maria Petrova and Ruben Enikolopov (2020), “Political effects of the internet and social media”, Annual Review of Economics, 12: 415–438.

Social media is bold.

Social media is young.

Social media raises questions.

Social media is not satisfied with an answer.

Social media looks at the big picture.

Social media is interested in every detail.

social media is curious.

Social media is free.

Social media is irreplaceable.

But never irrelevant.

Social media is you.

(With input from news agency language)

If you like this story, share it with a friend!

We are a non-profit organization. Help us financially to keep our journalism free from government and corporate pressure

0 Comments