India has witnessed a surge in severe fire and explosion-related accidents in industrial and commercial establishments, in recent years. In this post, R Nagaraj contends that perhaps the dilution – or rather the effective abolition – of industrial labour and safety regulations undertaken to boost India's rank in the World Bank's global index of Ease of Doing Business, may be the culprit.

On 25 March 2021, a fire broke out in a Covid-19 hospital located on the third floor of a commercial mall in suburban Mumbai, killing 11 patients. Reportedly, it took over 24 hours, working with 14 fire engines and 10 jumbo water tankers, to douse the fire. The cause for the fire remains unknown. In October 2020, in a similar Covid-19 facility in the same neighbourhood, a fire had killed two patients. Over the last two years, India has witnessed a surge in severe fire and explosion-related accidents in industrial and commercial establishments, exposing India's patchy safety record.

Let us recount a few ghastly accidents. On 21 January 2021, a fire broke out at Serum Institute of India in Pune – India’s only Covishield vaccine manufacturing facility – killing five workers and damaging machinery. A toxic gas leak at LG Polymers chemical factory in Visakhapatnam on 7 May 2020, boiler explosions at the thermal power plant in Neyveli Lignite Corporation on 7 May and again on 1 July 2020, and another boiler explosion at Yashashvi Rasayan Private Limited at Dahej in Gujarat on 3 June 2020, are a few prominent cases of industrial accidents. From January to August last year, India witnessed 25 serious industrial accidents killing 120 people and injuring many more.

In March 2021, the Union Labour Ministry informed the parliament that at least 6,500 workers lost their lives during the last five years while working at factories, ports, and construction sites. Official agencies may underestimate the loss of lives as they mostly fail to register accidents at smaller factories and worksites. In response to this, in April 2021, the Ministry has set up three expert panels to investigate the causes of the rising accidents and suggest remedies.

A cynic might quip that the official reaction to the accidents is predictable. They are soon forgotten, only to be overtaken by more severe disasters.1 Often lax regulation and oversight, inadequate and outdated equipment, and human negligence are the stock reasons, without fixing responsibility on either employers or concerned government authorities for dereliction of duty.

Changes in regulatory environment

What could account for the apparent spike? While the usual explanations may have merit, they probably ignore the significant changes in the regulatory environment made in recent years that may have contributed to the problem. I contend that perhaps the dilution – or rather the effective abolition – of industrial labour and safety regulations undertaken to boost India's rank in the World Bank's global index of Ease of Doing Business (EDB), may be the real culprit.

In 2015, the newly-elected government sought to address the industrial stagnation by initiating the national goal of ‘Make in India’ – to raise the manufacturing sector's share in GDP (gross domestic product) to 25% and create 100 million additional jobs in the industry by 2022. Expectedly, achieving this goal requires a massive step-up in investments, which policymakers believe, could mainly accrue from foreign capital. To entice global firms to invest, policymakers reckon that India needs to boost its rank in the EDB index. Hence, the central government – and its think tank NITI Aayog – single-mindedly focussed on improving its global position. The official ‘Make in India’ website makes the following claims: “India, today is a part of top 100 club on Ease of Doing Business (EoDB). FDI inflows in India stood at $45.15 bn in 2014-15 and have consistently increased since then. Moreover, total FDI inflow grew by 55%, i.e. from $231.37 bn in 2008-14 to $358.29 bn in 2014-20 and FDI equity inflow also increased by 57% from $160.46 billion during 2008-14 to $252.42 bn (2014-20)”.

The idea underlying the EDB index is simple. Economies perform poorly on account of excessive regulations for firms and terms of employing workers, and restricting the freedom of businesses to align their output with market conditions. Policymakers believe that India's labour laws are among the most rigid in the world, as commonly exemplified by the labour inspection system called "inspector raj". Employers and managers often complain that the inspection system is very demanding and is the root of corruption.2 It holds back the entrepreneurial spirit, driving away potential investors. As the burden of regulation increases with the size of the enterprise, firms often choose to remain small, thus sacrificing economies of scale in production.3 Firms, therefore, do not grow in size, failing to become global scale organisations.

Hence, in 2015, to simplify the conduct of business in the country, the central government practically abolished industrial safety laws, such as The Boilers Act, 1923 and Indian Boilers Regulation 1950 – vital regulations in the manufacturing sector. Earlier, the law required the boiler inspector to inspect factories periodically and certify the safety of boilers. This function was transferred to specialised 'third-party’ agents with the requisite expertise. The reforms also changed the compliance requirement under the Factories Act, 1948 – the cornerstone of the edifice of labour regulation. The legal obligation was moved from mandatory inspection by government inspectors – with powers to penalise the owner/manager for violating the factory laws – to self-certification by the owner/manager. Therefore, the changed rules view a factory inspector as a facilitator of business, and not an enforcer of labour laws to protect the interests and safety of workers.

An official order titled “Self-Certification-cum-Consolidated Annual Returns Scheme for Factories and Establishments in the State of Maharashtra”, dated 23 June 2015, stated the following:

“To perform a statutory duty cast on the [labour] inspectors … [they] are required to visit industrial establishments. With increased awareness among Employers & Employees in various establishments, it has been represented to the Government that employers themselves can discharge the responsibility of enforcing various labour laws in their respective establishments. The employers can also suo-moto certify the fact of correct implementation of the labour laws.

…the Government of Maharashtra has decided to introduce a new system for enforcement of various labour laws with simplification in maintenance of various records and registers required under different labour laws. The Government thus, introduces a self-certification-cum-consolidated annual returns scheme for various shops/ Establishment/Factories in the State. This step is intended to minimise enforcement visits of inspectors … while at the same time ensuring more effective compliance of various labour laws by the employers.”

Maharashtra's initiative soon became the national template for labour law reform. Self-certification is now the motto for most labour laws, as gleaned from the official websites of several state governments.5 Private agencies have sprung up to assist employers in complying with the simplified labour regulations.

A close perusal of the labour department websites describe the simplified procedures. However, they do not seem to report information on the compliance with the simplified labour laws and their outcomes for jobs, wages, working conditions, and workers' safety.

Interestingly, news reports suggested that third-party certification of boilers in Maharashtra has failed as no factory has received the certificate. None of the factories in Maharashtra complied with the self-certification scheme. In other words, subject to further verification, the reforms have effectively rendered labour and safety regulations toothless (Nagaraj 2019).

Hence, it seems reasonable to suggest that the recent rise in industrial accidents could be associated with the effective dilution of labour and safety regulations with the intention of boosting India’s EDB ranking. Unfortunately, trade unions (and industrial relations specialists) seem to have paid inadequate attention to the gravity of the changes initiated in the legal system to appease global capital.

Ease of Doing Business in India

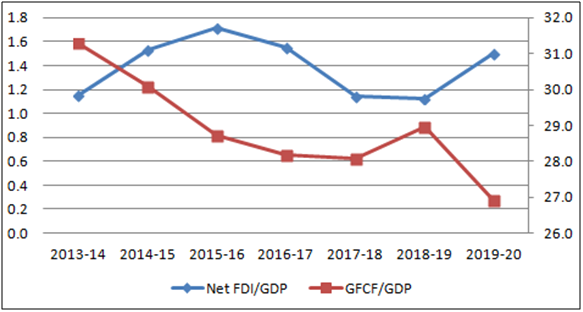

The preceding reforms have indeed succeeded in boosting India's EDB rank to 58 in 2020, up from 141 in 2014. Yet, they failed to augment foreign capital inflow, or more generally, increase domestic capital formation. As Figure 1 shows, net FDI (foreign direct investment) inflow as a proportion of GDP has hovered, between 1.1% in 2013-14 and 1.7% in 2019-20 (left-hand scale), without a discernible upward trend. Moreover, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) or fixed investment as a proportion of GDP has plummeted sharply: from 31.3% in 2013-14 to 26% in 2019-20 (right-hand scale). The implications of the unprecedented fall in the investment rate for GDP growth are hard to miss. It is no surprise that India’s industrial stagnation persists even after six years of launching the ‘Make in India’ initiative.

Figure 1. Net FDI and fixed investment, as a percentage of GDP

Notes: (i) The data are at current prices. (ii) Net FDI equals gross FDI inflow minus repatriation/disinvestment and FDI by India.

Sources: (i) GDP and fixed investment data are from the Economic Survey (2021). (ii) Net FDI data is from the RBI's Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy (2020).

Evidently, the dilution of the labour and safety laws – intended to improve the EDB index – is neither associated with higher foreign capital inflow nor improved domestic investment rate. Therefore, the underlying theory that the labour market rigidities are the principal reason for holding back foreign and private investment is questionable.

Why is it so? The EDB is a spurious index with little analytical and empirical foundation. There is no statistically valid association between a higher EDB ranking and higher foreign capital investment inflows in developing economies. To illustrate: Russia's EDB index rank moved up impressively from 120 in 2012 to 20 by 2018, with no investment inflow improvement. China's rank, in contrast, ranged from 78 to 96 between 2006 and 2017, but it excelled in attracting FDI.

Concluding remarks

So, one may wonder what India’s rising EDB ranking really achieved? It has apparently helped demolish the labour laws and safety regulations, thereby hurting the working poor and their livelihoods – without augmenting employment and output growth. The proposition that the labour market reforms positively affect employment and production is highly contentious, as the Indian policy debate can testify (Storm 2019).

With the scrapping of mandatory government oversight of safety regulations, no mystery, industrial and fire-related accidents have shot up. The labour reforms have seemingly ’rewarded’ India's working poor with greater workplace insecurity for helping India climb the ladder of ‘global best practices’.

Incidentally, the supposed accomplishment exposes entrepreneurial myopia. Firms fail to realise that workplace accidents raise insurance costs. Loss of skilled workers in accidents undermines productivity growth and profits in the long term. If the evidence and arguments laid out above have merit, then the government's single-minded attention to boost India's EDB index rank by knocking down the labour laws has failed to achieve the ‘Make in India’ goal.

The expert committees formed by the Ministry of Labour to look into the causes of the rising ghastly accidents mentioned earlier, should, I submit, investigate if the dilution of safety regulation could have contributed to non-compliance of safety rules.

Notes:

- On 23 April, there was yet another accident in a hospital near Mumbai, killing 15 Covid-19 patients, and one more accident on April 28, in Mumbra, near Thane, killing three patients. The Chief Minister of the state has ordered a probe into the matter with the opposition demanding a fire audit.

- Gurcharan Das, an ardent advocate of free market economics, writing in Foreign Affairs in 2006, said: “The "license raj" may be gone, but an "inspector raj" is alive and well; the "midnight knock" from an excise, customs, labor, or factory inspector still haunts the smaller entrepreneur.”).

- Arvind Panagariya is a prominent and vocal advocate of labour market reform to boost the manufacturing sector. In 2015, after being appointed as the head of the NITI Aayog, Panagariya said, “The inspector raj was curtailed by the introduction of self-certification, with inspections limited to a small sample of randomly selected factories. Red tape was cut for new businesses via the introduction of a single-window facility, ”For recent evidence questioning the inflexibility hypothesis, see Nagaraj (2018).

- For a non-technical account of the changes in the labour laws, see https://www.avantis.co.in/resources/acts/article/132/maharashtra-self-certification-cum-consolidated-annual-returns-scheme/

Further Reading

- Nagaraj, R (2019), ‘Make in India: Why Didn’t the Lion Roar?’, The India Forum, 3 May.

- Nagaraj, R (2018), ‘Of “Missing Middle”, and Size-based Regulation A New Frontier in the Labour Market Flexibility Debate’, CSE Working Paper 2018-7, Azim Premji University.

- Storm, S (2019), ‘The Bogus Paper that Gutted Workers’ Rights’, Institute of New Economic Thinking, 6 February.

0 Comments